Propaganda in the Time of COVID-19

Egypt's Bid to Rewrite the Narrative on Health Conditions and Medical Care Inside Places of Detention

March 8, 2021

By Kylee DiGregorio, senior researcher of the MENA Prison Forum

Editor’s Note: The following article was originally intended to be published on Thursday, 4 February. This, of course, did not come to pass in light of the assassination of writer, publisher, filmmaker, intellectual, and MPF co-founder, Lokman Slim. The text has been lightly edited to reflect this delay in publication, though it has not been modified to incorporate interim developments. Lokman’s editorial contribution to this piece was crucial, particularly in the shaping of its conceptual framework. The MENA Prison Forum dedicates this inaugural newsletter text to him. In memory of Lokman, and in honor of his vision.

“[W]e hope that all Egyptian hospitals are equipped with equipment like the ones inside the prison hospital.”

- Mohsen Awad, Member of the Egyptian National Council for Human Rights

As the history of Egypt’s “25 January Revolution” continues to be written, the annual commemorative groundswell of analysis tracing the country’s post-2011 arc of repression occurs this year against the backdrop of unprecedented, global attention on prisons. While the tenth anniversary of Egypt’s revolution came and went—and with it, National Police Day—political leaders around the world are continuously being called upon to limit their respective prison populations in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. This potentially damaging and altogether paradoxical confluence of events was not lost on the Egyptian regime, headed by defense minister turned president, Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi, who has presided over what is widely described as the most sustained and “relentless” crackdown in Egypt’s modern history.

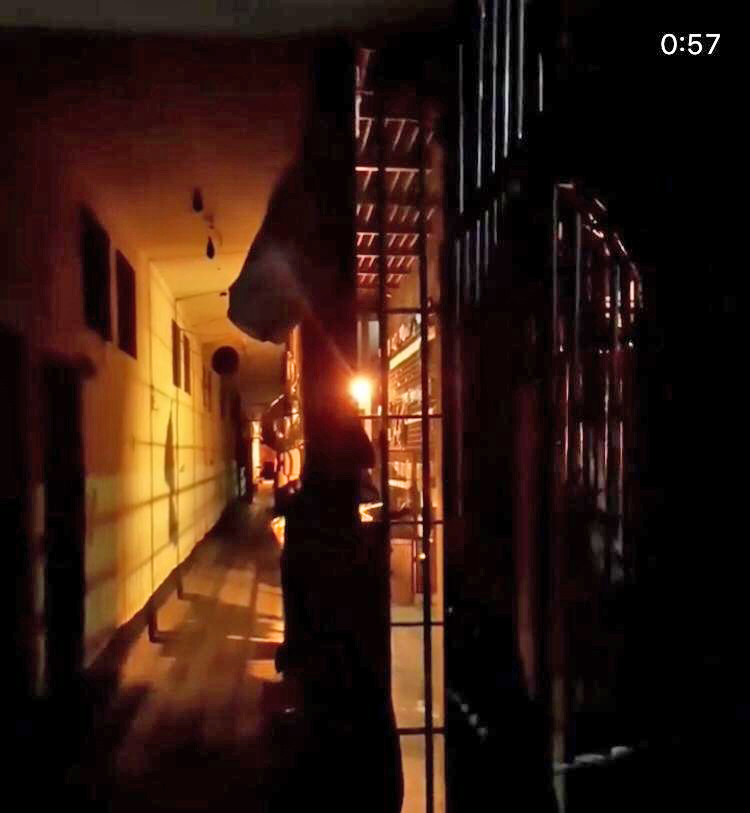

In a glaring attempt to deflect attention from this past month’s inevitable retelling of the developments that led “Generation Protest” to become “Generation Jail," the Ministry of Interior released the latest in a series of videos applauding the country’s “Prisons Authority Sector.” Posted to the Ministry’s YouTube channel on 18 January, the highly choreographed clip—running just over five minutes in length— is an unambiguous rejoinder to the elevated scrutiny that COVID-19 has invited upon detention facilities in general, and Sisi’s in particular. The curious timing of the video’s publication, in conjunction with its corresponding media campaign indicate a coordinated, preemptive public relations strategy aimed at refuting the “inhumane” conditions, medical negligence, and routine denial of health care detailed in Amnesty International’s most recent report. Though the full text was published on 25 January, to coincide with the revolution’s ten-year anniversary, Amnesty communicated the report’s findings to Egyptian authorities on 17 December, 2020. The Interior Ministry’s video—which is, for the first time, accompanied by English subtitles—appears to be the government’s only, albeit indirect, official response.

Despite Sisi’s robust efforts to control the narrative, such a video does less to rebrand the harrowing image of Egypt’s prisons than it does to reveal how ubiquitous, well-founded, and conceivably detrimental such notoriety in fact proves to be. That the regime deemed it necessary to produce such a clip stands as a testament to the rigorous investigations that have long been conducted into detention sites across Egypt, as well as to the political pressure that subsequent findings occasionally elicit.

One particularly concerted instance of international mobilization culminated in late October 2020 as 278 lawmakers throughout Europe and the United States openly denounced ongoing “violations of human rights” inside prisons and urged the Egyptian government to immediately cease its widespread practice of arbitrary detention. In two public letters addressed to President Sisi, these lawmakers framed their calls soundly through the lens of COVID-19. Fifty-six members of the US Congress implored Sisi to release prisoners of conscience “before their wrongful imprisonment becomes a death sentence due to the coronavirus pandemic.”

Yet conditions that are known to expedite the spread of the virus and exacerbate its risks—overcrowding, inadequate ventilation, poor hygiene and sanitation, insufficient or nonexistent health care and medical treatment, etc.—are features that have been synonymous with Egypt’s prisons for decades, long preceding the outbreak of COVID-19. The “utterly deplorable” levels to which such conditions have of course further deteriorated, however, stem from the sweeping campaign of arbitrary arrest and unlawful detention that Sisi has orchestrated since assuming power in June 2014. Likewise, as the regime’s dragnet expanded and Egypt’s prison population metastasized—now estimated to exceed 114,000 inmates—security forces implemented what, in November 2019, United Nations experts characterized as “consistent, intentional practices . . . that are severely infringing on [detainees’] right to life.”

Indeed, conservative figures published by the Committee for Justice (CFJ) report 873 deaths in custody between 1 January, 2014 and 1 December, 2019. In the first 100 days of Sisi’s presidency—between June and September 2014—the Nadeem Center for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence verified the deaths of 35 people in places of detention, primarily police stations. At the time, the Justice Ministry’s Forensic Medical Authority (FMA) attributed this rise in deaths to extreme overcrowding, which in turn was triggered by the influx of some 41,000 detainees whom had either been imprisoned, charged, or sentenced in the eleven months since Sisi’s July 2013 military coup that toppled the late former president, Mohamed Morsi.

In spite of—or perhaps, in part, due to—the diplomatic cooperation and overwhelming military support that Sisi habitually enjoys, neither the rate of arrest nor its fatal consequences have subsided. In the fall of 2019, security forces arrested more than 2,300 people in the span of just 12 days. An additional 920 individuals were held incommunicado. The operation—ordered in response to fresh anti-government protests—constituted the “largest wave of mass arrests” since late 2013. Only one month later, UN experts warned that “thousands of … prisoners in Egypt may … be at risk of death or irreparable damage to their health” because of the conditions under which they are held.

To situate appeals for prisoners’ release in terms of COVID-19 thus obscures the conclusion at which years of meticulous documentation has arrived: Detention in Egyptian state custody is, by definition, antithetical to one’s mental and physical health and bodily integrity.

As years of reports also demonstrate, this empirical reality is not the byproduct of passive negligence, but rather the quite predictable result of what can only be identified as a deliberate and systematic state policy. In a 2014 study examining conditions in 16 prisons and police stations across the country, the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) found that prison administrators routinely deny necessary medical care “as a punitive measure.” Human Rights Watch (HRW) conducted a separate investigation into deaths in custody throughout the same year. Among those who died were inmates with pre-existing health conditions including liver disease and cancer, but whom had nonetheless been denied requisite medical treatment over the full course of their detention. In a 2016 report detailing abuses specifically within Tora Maximum Security Prison—more commonly known as “Aqrab” (Scorpion)—HRW determined that the “regular interference” in detainees’ medical care “amounted to cruel and inhuman treatment.”

Such a conclusion should not come as a surprise when one considers the longstanding modus operandi of the Egyptian state vis-à-vis the individuals whom it detains and, frequently, disappears. During a 2012 television interview, which has since been removed, former Scorpion warden Major General Ibrahim Abd al-Ghaffar said that the prison “was designed so that those who go in don’t come out again unless dead.” Today, the facility holds between 700 and 800 prisoners. It is also located within the same Tora Prison Complex that encompasses Tora Lyman Prison—the site of the organized and well-rehearsed visit featured in the Interior Ministry’s 18 January clip.

To be sure, the denial of medical treatment is not limited to Scorpion Prison, nor is it a dated issue that Sisi’s regime has since acknowledged, much less remedied. Upon investigating 16 prisons in seven governorates between February and November 2020, Amnesty found that prison authorities “deliberately deny” detainees health care, and even withhold necessary medication that families provide, often “for the apparent purpose of punishing political opposition.” The devastating, yet wholly preventable, effects were borne out in research published by the Committee for Justice (CFJ). Of the 68 confirmed deaths in custody recorded by CFJ in the first six months of 2020, 51 were the consequence of a denial of health care. When such “willful” deprivation of medical treatment causes severe suffering and is intended to penalize or intimidate, or is based on any form of discrimination, Amnesty points out, it constitutes torture.

Again, this finding appears sadly unexceptional—even anticipated—if we recall that, in 2017, the UN Committee against Torture drew “the inescapable conclusion that torture is a systematic practice in Egypt.” The nature of the torture addressed by the Committee, however, was not that of intentional medical neglect, but rather assumed the more ‘conventional,’ explicit form. Setting aside for a moment the matter of “purpose,” torture as it is defined by the UN Convention Against Torture—to which Egypt is a party—is, in part, “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person . . . by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.” Torture then, in its most elementary demarcation, might be conceptualized as the active dismantling and destruction of an individual’s mental and physical integrity. In short, it constitutes a categorical subversion of bodily health and psychological wellbeing and, by extension, a flagrant violation of an individual’s non-derogable right to such.

And yet, this grave infraction is—as the Committee against Torture spells out—perpetrated by Egypt’s police and military forces, National Security Agency (NSA) officers, and prison guards, and is facilitated by the near “universal” impunity afforded to them by public prosecutors, judges, and prison officials and administrators. Human Rights Watch reiterated these findings in a report delineating what it characterized as the regime’s “assembly line of torture,” which is aimed at extracting false, often pre-written confessions that are subsequently used as ‘evidence’ in fabricated cases against real or perceived political dissidents. As the rights organization documented, members of the public prosecution not only fail to investigate allegations of torture, but “explicitly or implicitly endorse its use.” According to the Committee against Torture, this process implicates each facet of the criminal justice system, and is “habitual, widespread and deliberate.” It is therefore likely that torture as it is meted out in Sisi’s Egypt constitutes a crime against humanity.

Cultural theorist Elaine Scarry wrote in 1985 that torture is a practice that “allows real human pain to be converted into a regime’s fiction of power.” It is “precisely because the reality of that power is so highly contestable, the regime so unstable,” she adds, “that torture is being used.”

These words were affirmed on 25 January, 2011, when Egyptian youth organized protests to undermine National Police Day celebrations and to call for the resignation of General Habib al-Adli, under whose leadership the Interior Ministry had become, as scholar Salwa Ismail notes, “the most feared and despised apparatus of government.”

Egypt’s current Interior Minister, Major General Mahmoud Tawfik—who has himself overseen the arbitrary arrest and torture of dozens of children and youth since his June 2018 appointment—seems nevertheless to be tasked with projecting a second, diametrically opposite fiction, tailored for western consumption. So of course, one might reasonably speculate that the calculus behind the Interior Ministry’s latest media campaign derived from the regime’s years-long contracts with multiple American public relations firms. As a journalist for Egypt’s state-owned, English language Ahram Online candidly ceded, the country’s Prisons Authority has been “keen” to arrange visits like that filmed in the 18 January clip “in a bid to drive people, especially foreigners, away from believing the negative rumours concerning prisons in the country.”

Yet, as Sisi’s western audience is left to parse fact from fiction, reality from “rumour,” one might consider applying the line of thought underlying Scarry’s theory: Perhaps it is precisely because the reality of health care—including COVID-19 treatment—is so highly contestable, prison conditions so abysmal, that carefully crafted videos are being produced, disseminated, and lauded.

Egypt’s quasi-governmental National Council for Human Rights (NCHR) reported in 2016 that prisons were 150 percent over capacity and police stations and security directorates 300 percent over. Such acute overcrowding, the Council added, was further aggravating a host of chronic issues, including a “lack [of] medical care, medicine, food and even areas for rest or sleep or health services relevant to day to day living.” In 2018, NCHR member George Ishak publicly stated that torture had become “increasingly intolerable,” prompting the Council to advise legislators and executive authorities to amend relevant laws within the Penal Code. Even so, the Interior Ministry’s 18 January clip features a remarkable sound bite delivered by Mr. Ishak’s colleague and fellow NCHR member Mohsen Awad, who seems to suggest that Egypt’s prison hospitals are the best in the country.

However ridiculous Mr. Awad’s claim, it is inadvertently telling—both as a grim indication of life under Sisi’s rule, and as a kind of Freudian slip. In drawing a comparison between conditions in and outside of prison that deems the former preferable, Mr. Awad is revealing the political psychology on which many authoritarian regimes across the MENA region have been constituted and from which they continue to be consolidated. Driven, first and foremost, by their own self-preservation, such regimes have long favored institutions that serve the state’s capacity for coercion and social control. The prison has therefore come to represent the depraved standard to which regimes aspire, and thus the design on which societies are modeled.

In such a framework, in which a healthy and vibrant civic space is perceived as an existential threat to state survival, the prevailing ‘policy’ will always be one of mass arrest, arbitrary detention, and extrajudicial killing. Because, through the eyes of such regimes, an active civil society is the deadliest virus of all.