Shedding Light on the Campaign behind the Establishment of the Independent Institution on Missing Persons in Syria

By Amany Selim

December 29, 2025

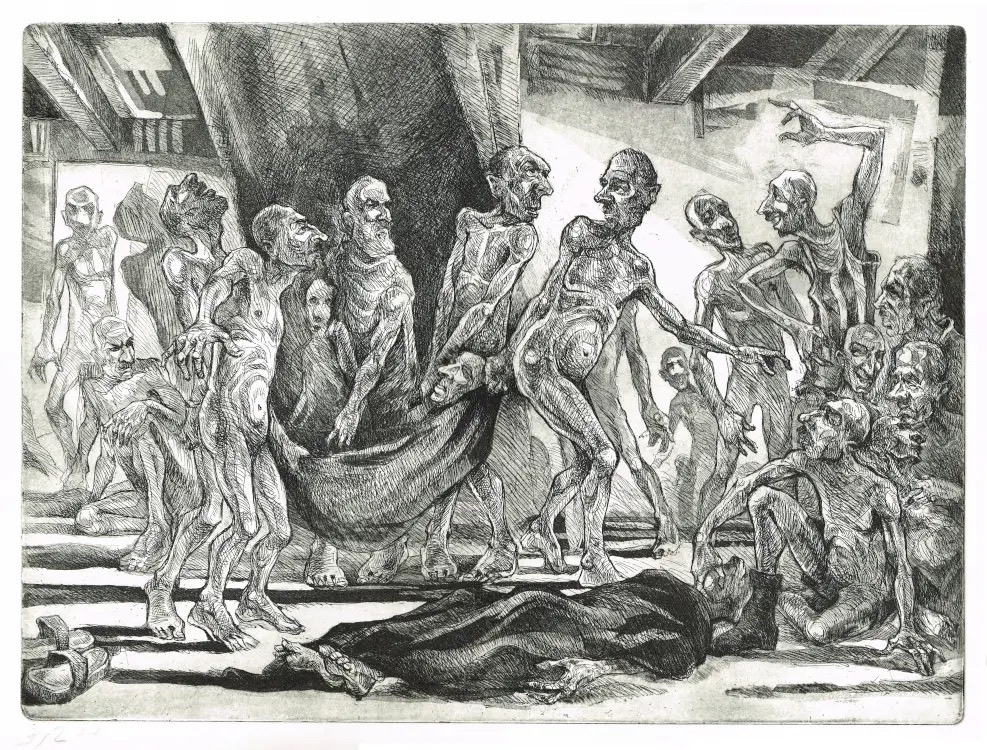

Artwork: Courtesy of Najah Albukai

Introduction

After the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024, the search for the forcibly disappeared and missing persons became a key issue on the agenda, as it is estimated there are over 180,000 missing persons in Syria. Typically, this search emerges after the end of conflicts, as societies move toward processes of recovery and reconciliation. What distinguishes the Syrian case, however, is that this process began before the end of the Syrian conflict and the abrupt fall of the regime. In June 2023, the Independent Institution on Missing Persons in Syria (IIMP) was established by the UN General Assembly through a resolution that was endorsed by 83 member states. This development was the outcome of a two-year mobilization by Syrian survivors and family members’ associations who were keen on seeking truth and justice for their loved ones at a time when the regime was still in power and its fall seemed unforeseeable.

This institution came to life in April 2024 and its role became particularly significant as its establishment coincided with the fall of the Assad regime a few months later. In theory, the regime’s end enabled the IIMP to access areas previously under its control; something that would not have been otherwise possible and that had been long anticipated as a hurdle to the institution’s work.

What led to the establishment of such an international institution that is now entrusted with an incredibly difficult task? Drawing on conversations with stakeholders who were directly involved in mobilizing for the establishment of the institution, this text will trace the story of how they successfully mobilized the UN system to attain their goal of establishing a mechanism dedicated to the right to truth. The establishment of this institution not only demonstrates the leadership of affected communities and their ability to actualize their vision, but it also sets an important precedent. The IIMP formally embeds the meaningful participation of victims and survivors within its system and takes a victim-centered approach to its mandate. Therefore, it is important to shed light on the campaign that enabled this outcome, while acknowledging the central role played by Syrian survivors and family members’ associations in making this happen.

Strategic Mobilization of the UN System

Survivors and family members’ associations, together with their trusted partners from local and international organizations, approached the UN in 2021 with the demand to establish a mechanism for determining the fate and whereabouts of the disappeared. They envisioned the mechanism as a means of achieving the right to truth, with families of victims directly involved to ensure meaningful participation. The coalition relied on a range of strategies and tactics to push their demand through the UN system. First, they made a deliberate decision to engage the UN General Assembly instead of the Security Council, as the latter would have blocked their demand with a veto. Furthermore, the General Assembly includes a larger number of member states, allowing for an opportunity to mobilize on a larger scale.

Simultaneously, they lobbied for the incremental inclusion of the concept of “meaningful participation of victims” in the search through a series of UN Human Rights Council resolutions to support their advocacy work for establishing a mechanism. In doing so, and as stakeholders tended to emphasize in my conversations with them, they transformed their demand for victims’ participation from a discursive claim rooted in victims’ advocacy, to one with a legal basis.

Third, and most importantly, the sequence through which the coalition-built momentum within the system also mattered. The coalition appealed to the Third Committee in the UN, which deals with human rights issues, to request in its briefing the Secretary General to conduct a study on how to strengthen efforts to establish the fate and whereabouts of the disappeared in Syria. The request was endorsed by the Secretary General himself, giving the report authority and weight when it concluded that a dedicated mechanism for searching for the disappeared is indeed needed in the Syrian context and that this mechanism should meaningfully include survivors and their families in the search process and consultations. Securing the Secretary General’s authorization for the study allowed the coalition to use its favorable recommendation as tangible evidence to rally support among member states for their demand for a mechanism.

Fourth, the coalition was keen on drawing cross-regional support for the establishment of the institution. In particular, they avoided seeking support from traditional countries, including Western countries, recognizing that this might have politicized their demand and polarized support around it. Instead, they invested in building relationships with global majority countries, especially in Latin America, given their own history with enforced disappearances. Furthermore, they also sought to engage less politically involved states in Europe, such as Luxembourg, to serve as the ‘Penholder’ or the state leading the drafting of the resolution and rallying support among state members for voting.

Lastly, all throughout this process, families and survivors were at the center of every move; meeting with diplomatic missions, deliberating with partners, and speaking at side events and UN forums, which gave the campaign a strong sense of being truly survivor and family-led. Indeed, this was the campaign’s greatest strength that it genuinely reflected the wishes of survivors and victims’ families and was ultimately led by them.

Conclusion

The UN system is a deeply bureaucratic system, yet the coalition of survivors and family members’ associations advocating for the IIMP approached it creatively. From choosing the General Assembly as a channel for their demand, to building support among global majority countries, to keeping families and survivors at the front of the work, the coalition employed various tactics and strategies that effectively mobilized the system to their advantage. The leadership of Syrian survivors and victims’ families has been key to the establishment of this institution and institutionalizing the participation of families in search processes. The IIMP has commenced its work and what remains to be seen is how it will collaborate with national institutions and fulfill its promise of setting a precedent in ensuring the meaningful participation of families.

Amany Selim holds a PhD in Sociology from the University of Bergen, Norway, and is currently an Associate Researcher at the Centre for Humanitarian Leadership (CHL) at Deakin University. Her research interests include social movements, the sociology of emotions, and diaspora studies.