Alaa Abdel Fattah

The Politics of Prison Writings

October 31, 2021

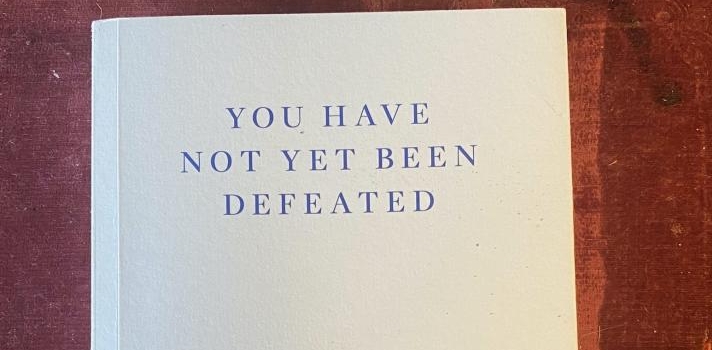

You Have Not Yet Been Defeated

Iconic Egyptian engineer, political activist, and prisoner Alaa Abdel Fattah recently published a book that opens a conversation about the politics of prison writings, its purpose, and its expected audience. “You Have Not Yet Been Defeated” is a collection of Alaa’s essays, articles, and social media posts since the 2011 uprisings in Egypt, including materials he wrote while detained. Fattah, who has been incarcerated several times and has spent many years behind bars both before and since the significant political change Egypt underwent in 2011 presents “not only a “unique account from the frontline of a decade of global upheaval,” but also “a catalogue of ideas about other futures those upheavals could yet reveal.”

Fattah’s book belongs to a long history of prison writings that include ethnographic accounts, memoirs, and attempts to theorize cultures and histories of incarceration in the Middle East. His writings fuse two types of writings that cover the Middle East region in general: there are two schools of thought that grapple with the broader questions of why we write and whom we criticize when we set our arguments. First, there is the school connected to the colonial legacy that politically, culturally, and economically still controls and produces images about the non-white “other” in the global south. This school gives more attention to hegemonic orientalist Western perceptions about the Middle East, and it is needless to mention that many members of the first school are also connected to Western ‘critical’ and ‘secular’ universities and research institutions. Hence, scholars and writers who belong to this school incur the responsibility to highlight modes of resistance to and critique of the Western secularist understanding of the Middle East as essentially repressive and non-modern. With respect to prison writings in specific, this school seeks to further dig into the roots of authoritarian ruling in the Middle East and to link it to broader historical processes of political, economic, and social exploitation of the global south.

While some of Fattah’s writings join this kind of critique, he is aware that hegemony means different things in various contexts. Middle Eastern governments currently claim to be sovereign, they can employ their power to further repress internal opposition forces. This brings us to the second school of thought of scholars and writers who situate their arguments within theoretical frameworks that address modes of resistance against other non-Western social and political forces. Members of this school emphasize that while some of the grievances of the Middle East might be attributed to the West and its hegemonic discourses, others should be studied via a critique of fascist military and Islamist regimes that for decades have been exploiting and crushing their citizens’ bodies and souls. When it comes to prison writings in particular, this school does not always think that the West is ‘evil’ but instead that activists in the Middle East can capitalize on what Western governments have achieved on the levels of human rights, accountability, and democracy to reflect the brutalities of their regimes. The fact that elements of the book were translated from Arabic but that the book can be only found outside, not inside, of Egypt, presents a dilemma of how atrocities of Middle Eastern rulers can be spoken about within the countries they occur. The book and other prison writings coming from the Middle East are in general celebrated in Western countries and via Western media is a message to activists and researchers in the region to further build means of cooperation and partnerships with Western universities, civil society organizations as well as governments.

Criticizing the West and its imperialist interests in the Middle East does not mean to forget about the critical forces that financially and politically support the moral causes of Middle Eastern activists. Fattah’s book and its impact put the concerns of the two schools in consideration while teaching us about meanings and effects of being ‘critical’ in a country like Egypt. It is vita; to note that the book has been published at a time when Fattah has been recently considering suicide in prison due to his deteriorating mental health. We hope the book, which Alaa’s family members and friends edited and translated, will give some hope to whom historian Khaled Fahmy called “the freest Egyptian.”