Maspero Massacre

A Reading of Coptic Theology in Egyptian Prisons

October 13, 2021

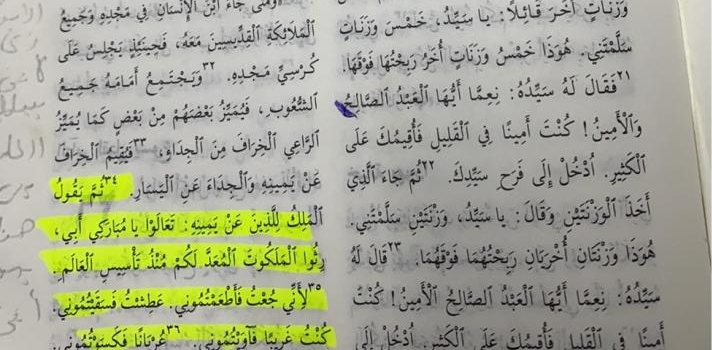

A photograph of Mark’s Bible, Gospel of Matthew, with his annotations during his detention.

Earlier this week marked ten years since the Maspero massacre when 28 Coptic Christians were killed by the bullets and the tanks of the Egyptian army. On October 9, 2011, Copts organized a demonstration in response to the demolition of a church in Upper Egypt. In front of the Egyptian state television, known as Maspero, the Coptic community witnessed the worst state-sponsored massacre in its modern history.

In addition to the causalities and the dozens who were injured in the aftermath of the Maspero massacre, Egyptian authorities detained a number of Coptic (and Muslim) activists who supported the protest. On the condition of anonymity, one of the detained Copts accepted to speak to our project coordinator Mina Ibrahim. During his fieldwork in 2018, Mina met Mark (a pseudonym), who has lived in a European country since 2017. After failing to re-integrate into his neighborhood parish or to make sense of his grievances after his release, Mark decided to leave both his home country and his political activism. He got married and has two children, who he wishes to have a better and more fortunate life than his difficult experience in Egypt.

In October 2011, Mark was captured and accused of causing public agitation and disorder in the country. He spent four months in jail and was released around the Eastern Christmas on the 7th of January, 2012. He did not go to the Christmas Eve prayer he usually attended every year; not only because he did not want to meet his acquaintances at his neighborhood parish, but also because he was busy reading and thinking about the notes he added on the margins of his Bible during his imprisonment. With his pencil and fluorescent marker, he commented on stories he used to take for granted when he was a kid in Sunday School.

In fact, the clerical leaderships of the Sunday School – the official educational institution of the modern Coptic Orthodox Church – failed to curate a theology applicable to prison experiences. Although settings of detention and incarceration are highly present in the Bible and in the lives of its saints, martyrs, confessors, and apostles, and even of Jesus himself, there are not regular discussions of the role of contemporary prisons in cultivating the Coptic Christian faith and identity. While elements of Mark’s experiences of religious persecution in a land not far from where Christian leaders first struggled for their religion, the notes in Mark’s Bible from his detention show a personal, conscious reckoning with parallelism more than 2000 years apart. Mark’s insights challenge the theological and political of the Coptic Church institution, as well as the alliance of the latter with the Egyptian State. Moreover, they question meanings of the punishment and discipline practiced by God, the Church, and the Egyptian State. Last but not least, Mark interrupts aspects of repentance and confession that he has particularly learnt via the famous biblical parable of the “Prodigal Son.”

- “But during the night an angel of the Lord opened the doors of the jail and brought them out” (Acts 5:19).

Mark comments: “Who can bring me out? The Egyptian prisons seem more resistant to miracles than the Roman ones during the first days of Christianity. Is it because the Egyptian military allies with the Church? I do not know if Jesus is confused about whether I should be rescued and released like the Apostles, or is it because the Egyptian security forces are more powerful than him.”

- “But the Lord was with Joseph in the prison and showed him his faithful love. And the Lord made Joseph a favourite with the prison warden” (Genesis 29: 31).

Mark comments: “Joseph was innocent, or so we learned at Sunday School. God put him into jail because he had a better plan for him. This is what we learned at the Sunday School. But I do not know God’s plan for me?!! Maybe, Joseph also did not know God’s plan, as I do not know mine. I won’t be a prime minister like him [Joseph was second in command to the Pharaoh that is equal to today’s prime minister] because I am Coptic. I will also be an ex-prisoner in a few months (or maybe years???). Jesus, my prison warden is so wicked. Why did not I get one like the one that Joseph had?”

- “From inside the fish Jonah prayed to the Lord his God. He said: “In my distress I called to the Lord, and he answered me. From deep in the realm of the dead I called for help, and you listened to my cry. You hurled me into the depths, into the very heart of the seas, and the currents swirled about me; all your waves and breakers swept over me”” (Jonah 2: 1-3).

Mark comments: “Did Jonah pray to get released from inside the fish? Or did he pray to be forgiven for escaping God’s plan? God asked Jonah to ask sinful people to repent, and Jonah did not execute this plan. Did my participation in Maspero (the demonstrations in October 2011) was against his plan? What is his plan from the beginning? I want to know it, so I do not feel that he is punishing me like what he did with Jonah. God was speaking directly to Jonah, but I cannot hear his voice. I think Jonah was quite sure that God would listen to him because he was already speaking to Him. But now, God speaks to us through the Coptic Church priests and Pope. How can I know what God wants to tell me, if the Church is in alliance with the military that killed us?”

- The soldiers led Jesus away into the courtyard of the palace known as the governor’s headquarters, and they called together the whole company of soldiers. They dressed him up in a purple robe and twisted together a crown of thorns and put it on him. They saluted him, “Hey! King of the Jews!” Again, and again, they struck his head with a stick. They spit on him and knelt before him to honour him. When they finished mocking him, they stripped him of the purple robe and put his own clothes back on him. Then they led him out to crucify him” (Mark 15: 16-20).

Mark comments: “Jesus himself was imprisoned. His imprisonment preceded his crucifixion. I think this was an important part of his salvation plan. He died for our sins, but this came after he was tortured in the prison. Will my imprisonment precede a better future like Jesus’s resurrection? I do not know when I will be released. I have been here for two months. Jesus was just imprisoned for one night, and they killed Him the following day. I think Jesus was lucky that his imprisonment duration was short and that it was quickly followed by the most splendid event in the history of the whole world. But here in this prison, everything is stagnant and the time does not move. Nothing better seems to come. I am afraid. No resurrection would happen in this dark cell.”

- "Then the King will say to those on his right, 'Come, you who are blessed by my Father; take your inheritance, the kingdom prepared for you since the creation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me'” (Mathew 25: 34-37).

Mark comments: “I am happy with the Church’s service devoted to taking care of prisoners. They visit us here once a week on Sunday to allow us to confess and to receive the communion. I am happy that I can still pray in the prison, but the priest treats me as the prodigal son, who returned back to his father after losing his money due to his wrongdoings. What did I do wrong? I was protesting against the demolition and burning of churches, the houses of God. I am confused. I feel lost. What is right and wrong? I really do not know. For what should I repent? For what I should be forgiven? Lord have mercy.”