PRISON NOTEBOOK (Excerpts)

By Ibrahim El-Salahi

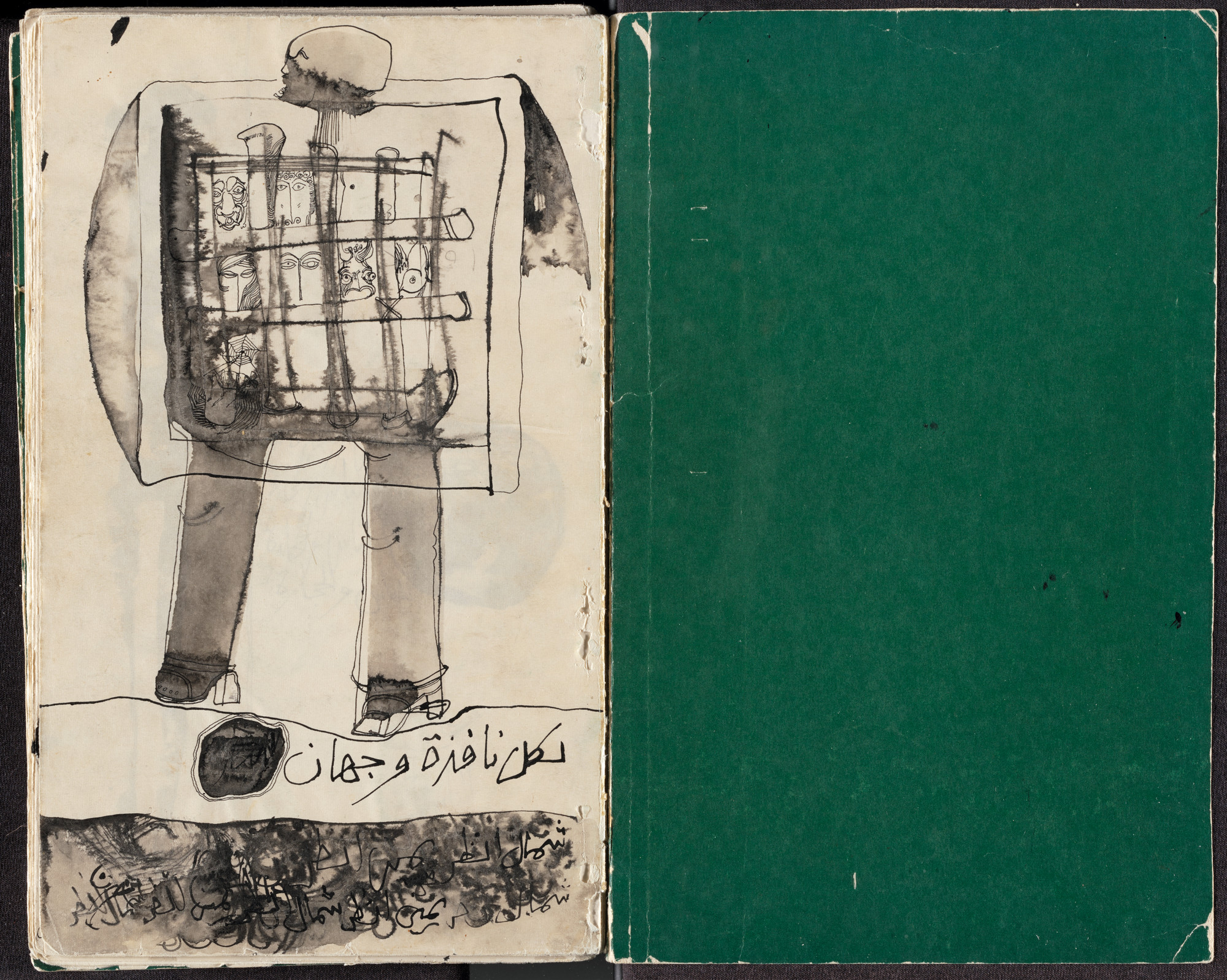

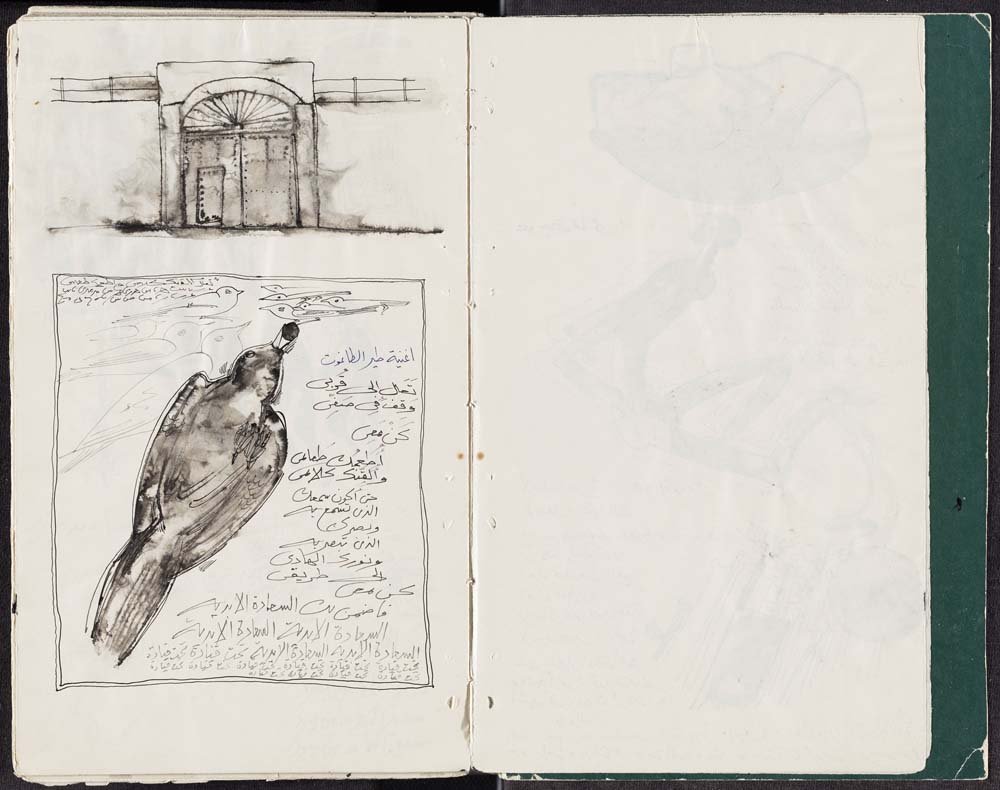

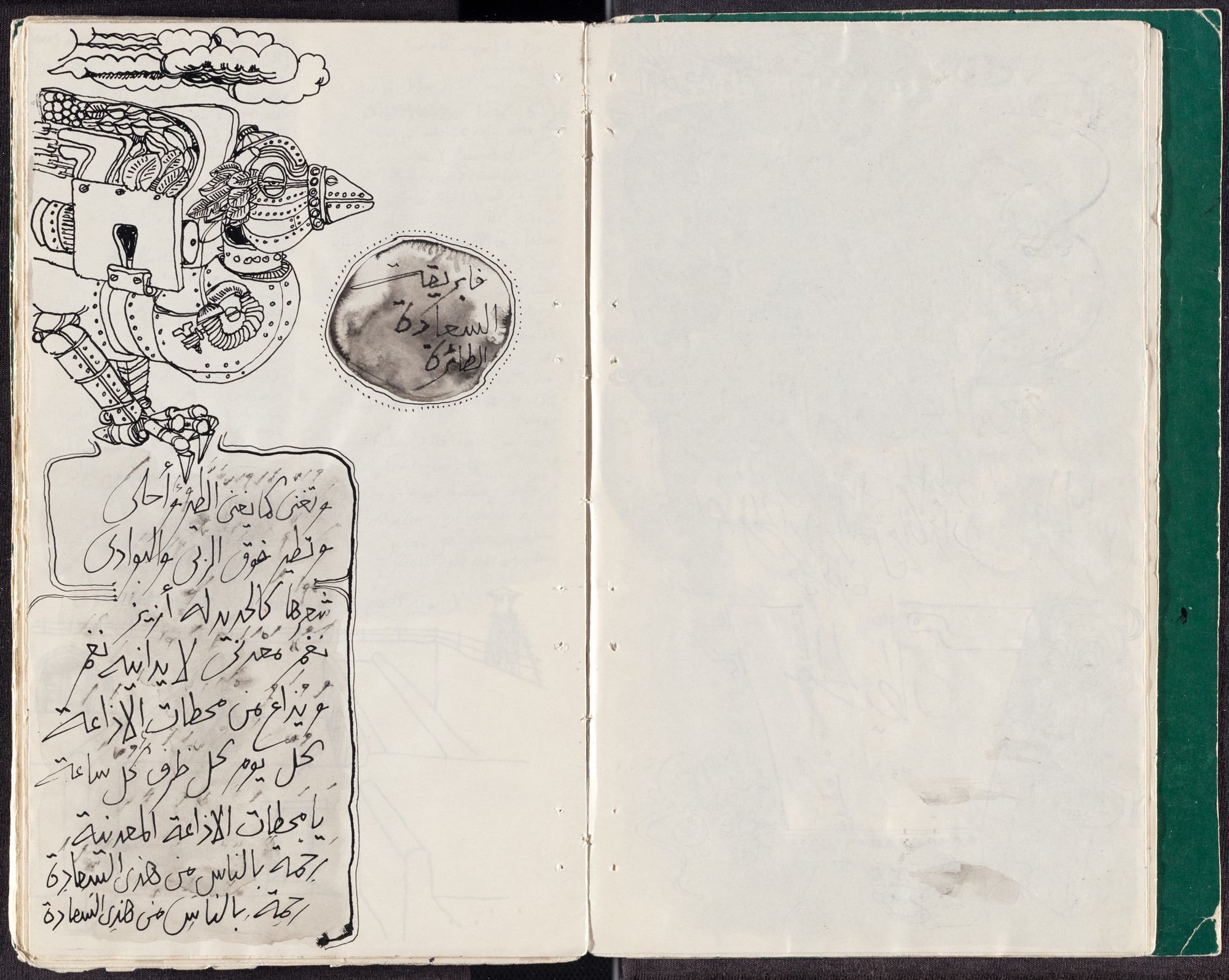

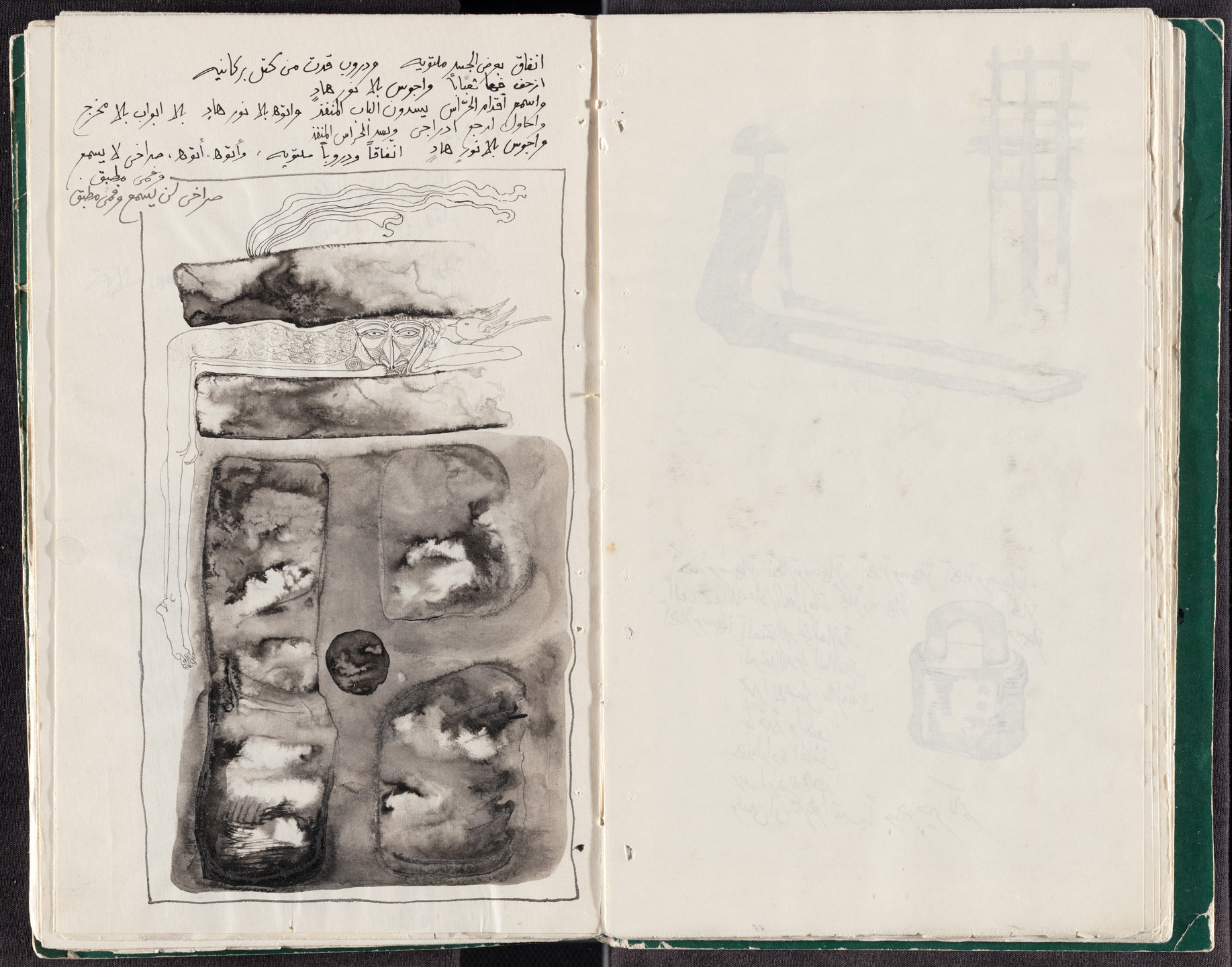

The highly esteemed Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi produced these pen-and-ink drawings—accompanied by his own Arabic prose and poetry, as well as Qur'anic verses—as a means through which to record and ultimately exorcise his experience inside Khartoum's notorious maximum-security Kober prison. While serving as Sudan's Undersecretary of Culture in September 1975, El-Salahi was wrongfully accused of involvement in plotting an anti-government coup. He was subsequently beaten, and imprisoned without charge or trial for six months and eight days. In published excerpts from his private memoir, El-Salahi outlines the conditions in which he lived throughout his imprisonment: . . . continual interrogation, lack of proper food or medicine, no beds, ant and mosquito bites, and an ever-filling and overflowing bucket [normally used as a toilet]. In such degrading circumstances, he writes, "each day was like a year of torture, inhumane humiliation, and misery."

Following his release from Kober, El-Salahi was placed under house arrest. It was over the course of this period that he filled the 38 pages that would become Prison Notebook. His motivations for doing so were both personal and collective. He writes in his unpublished memoir: I must have intended then . . . to cleanse myself of any residue of bitterness that may have accumulated within me. . . . I must have tried through abstraction to understand or to make sense of why things unexpectedly happen to us, and bring some order back into my system. Yet, in Prison Notebook—which is now referred to as his "visual memoir"—El-Salahi explains: I started to record [my prison experience] so as not to forget. Not only for me but for anyone who is innocent and has been imprisoned under false pretenses. Just to remember what can happen.

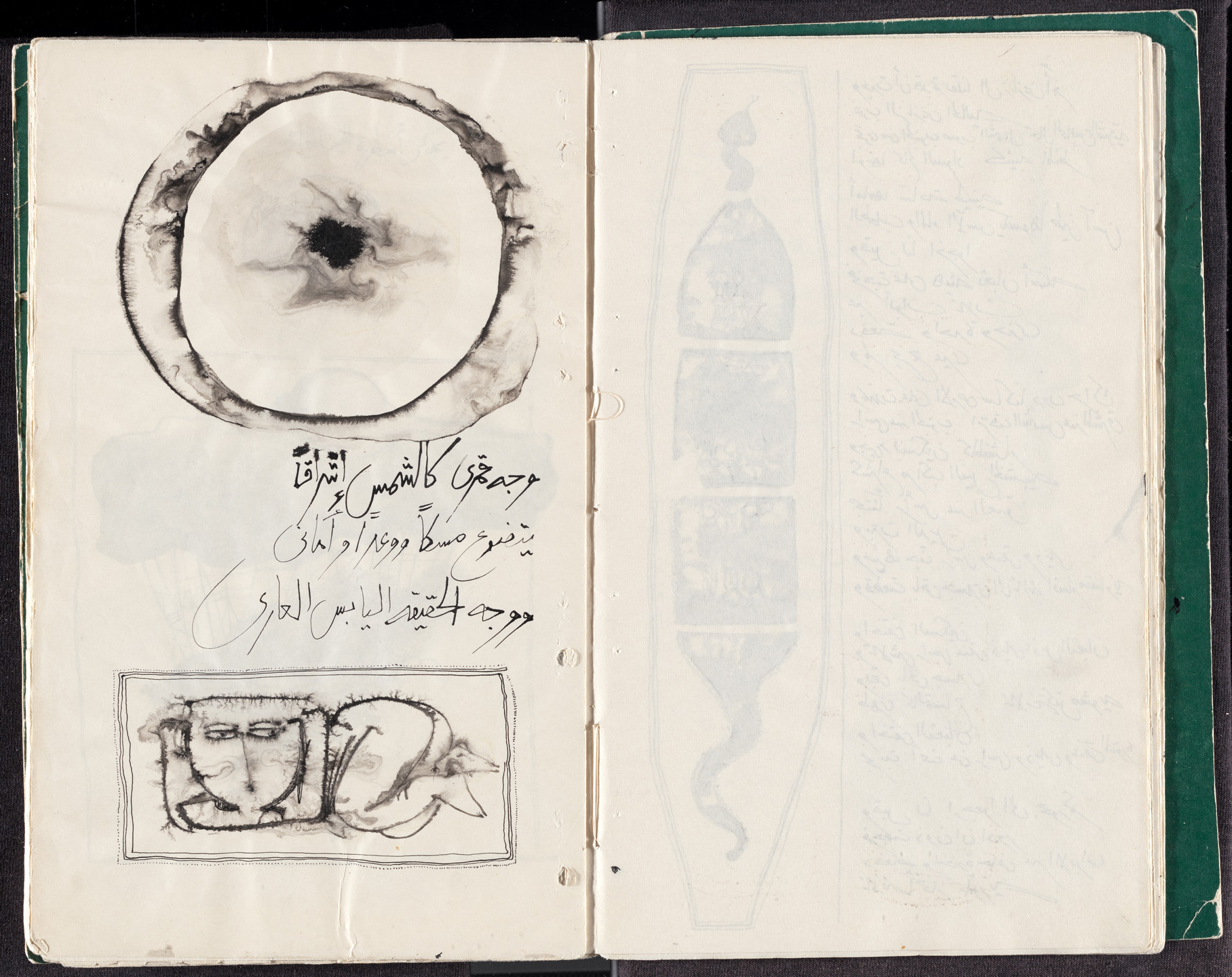

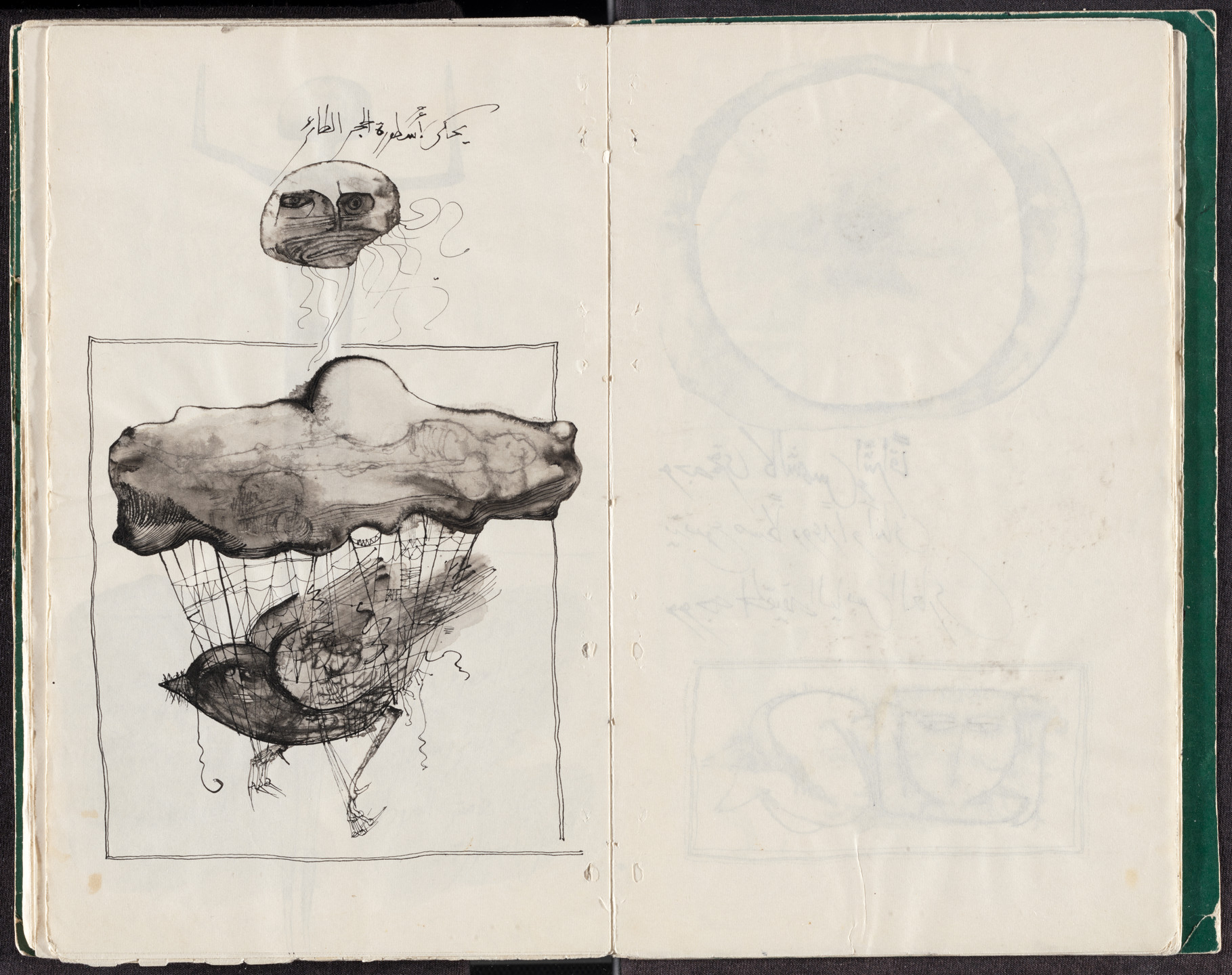

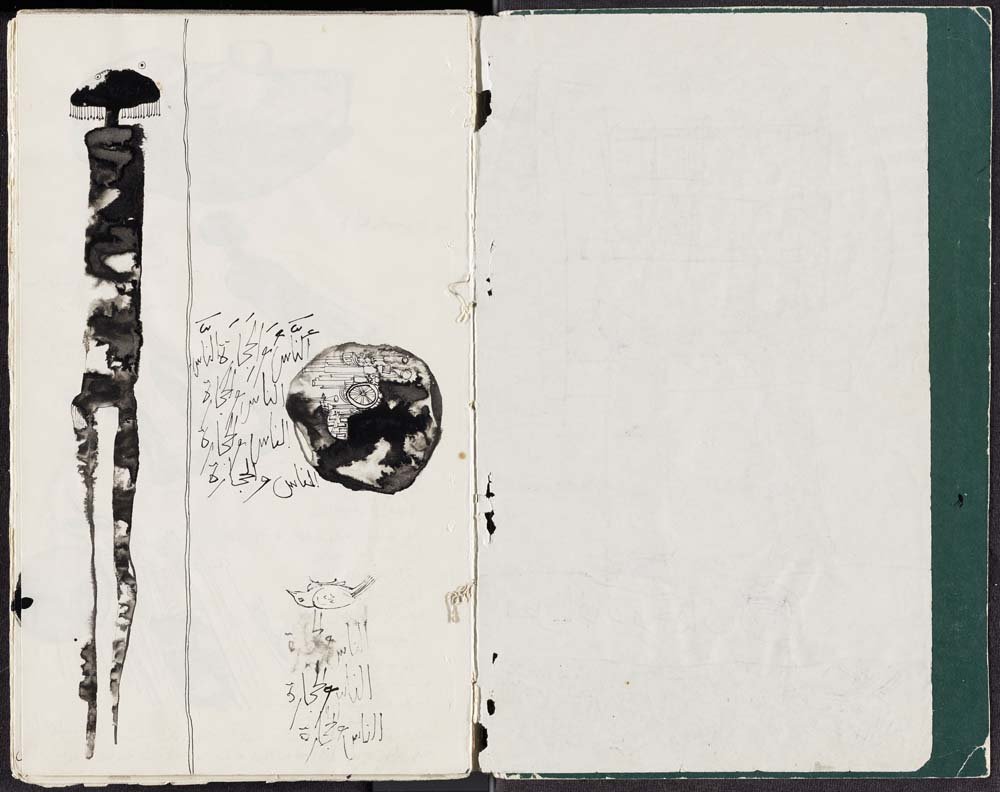

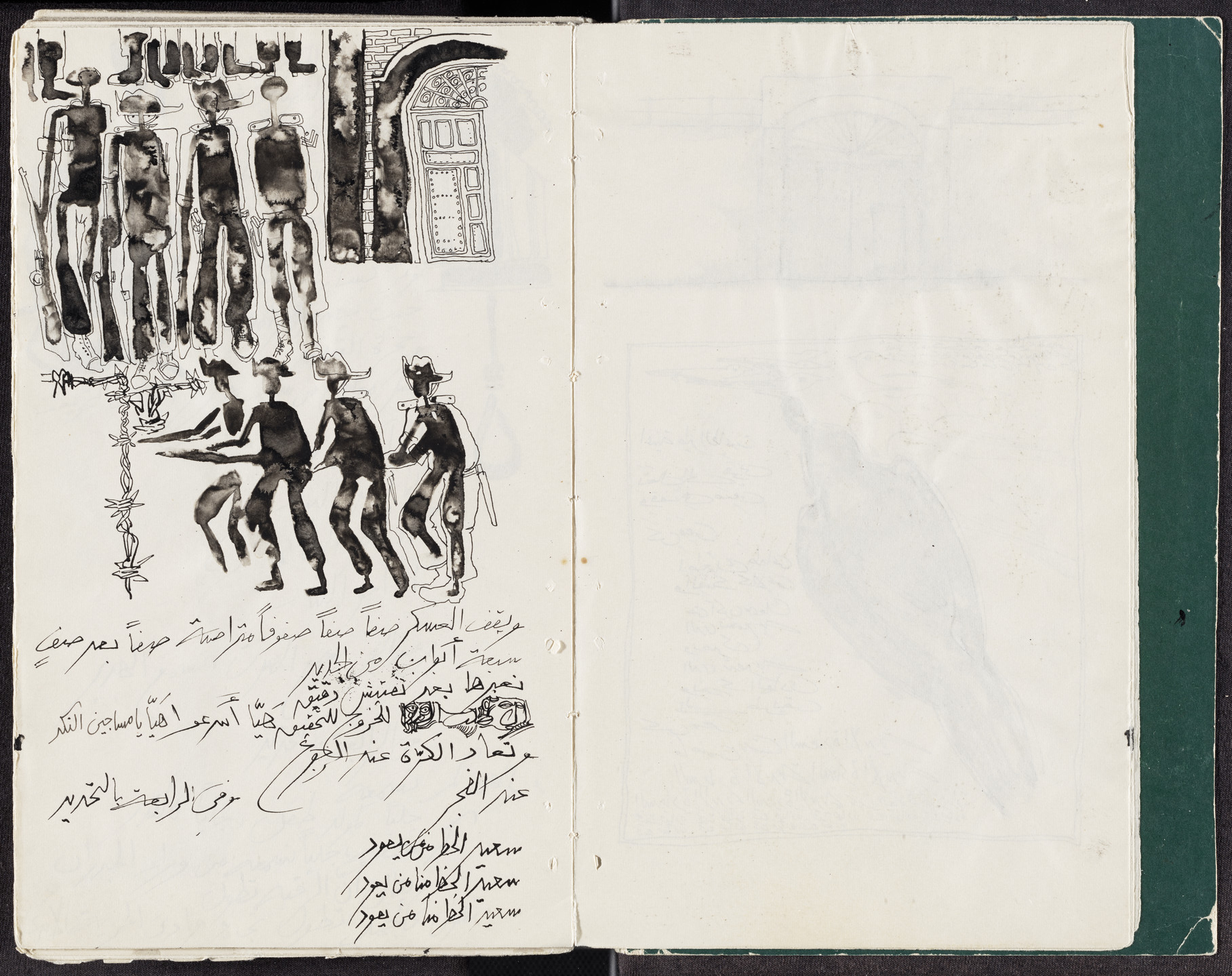

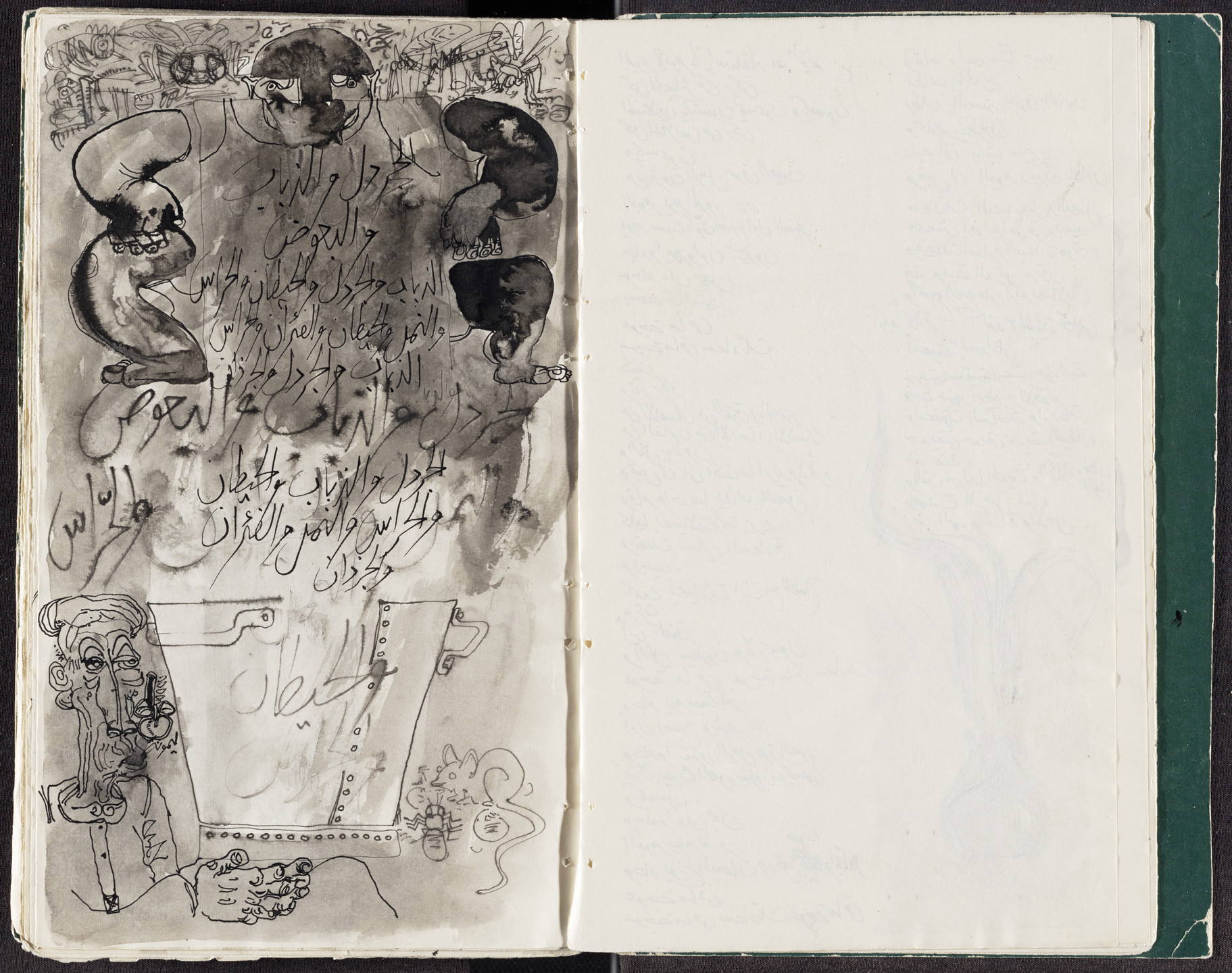

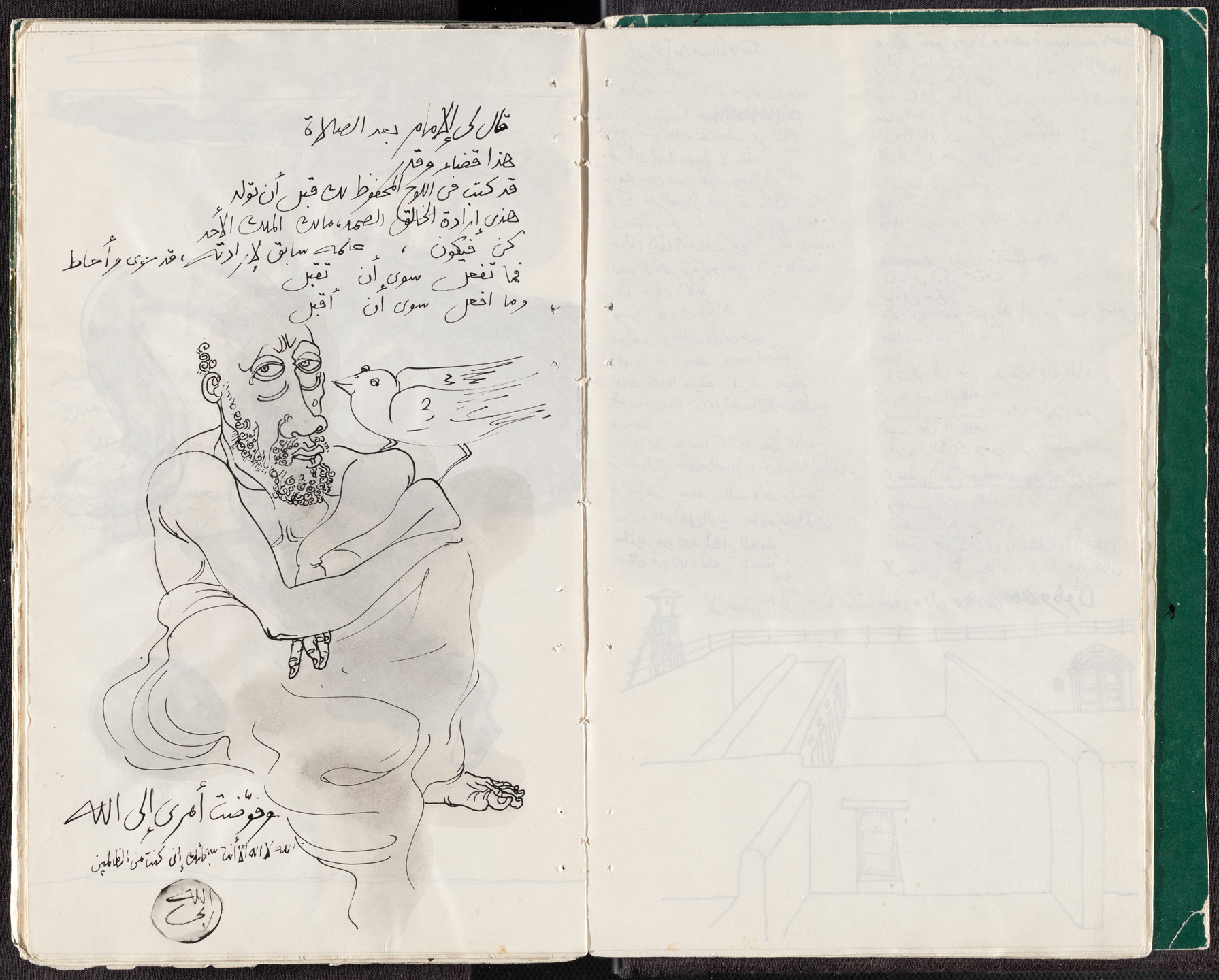

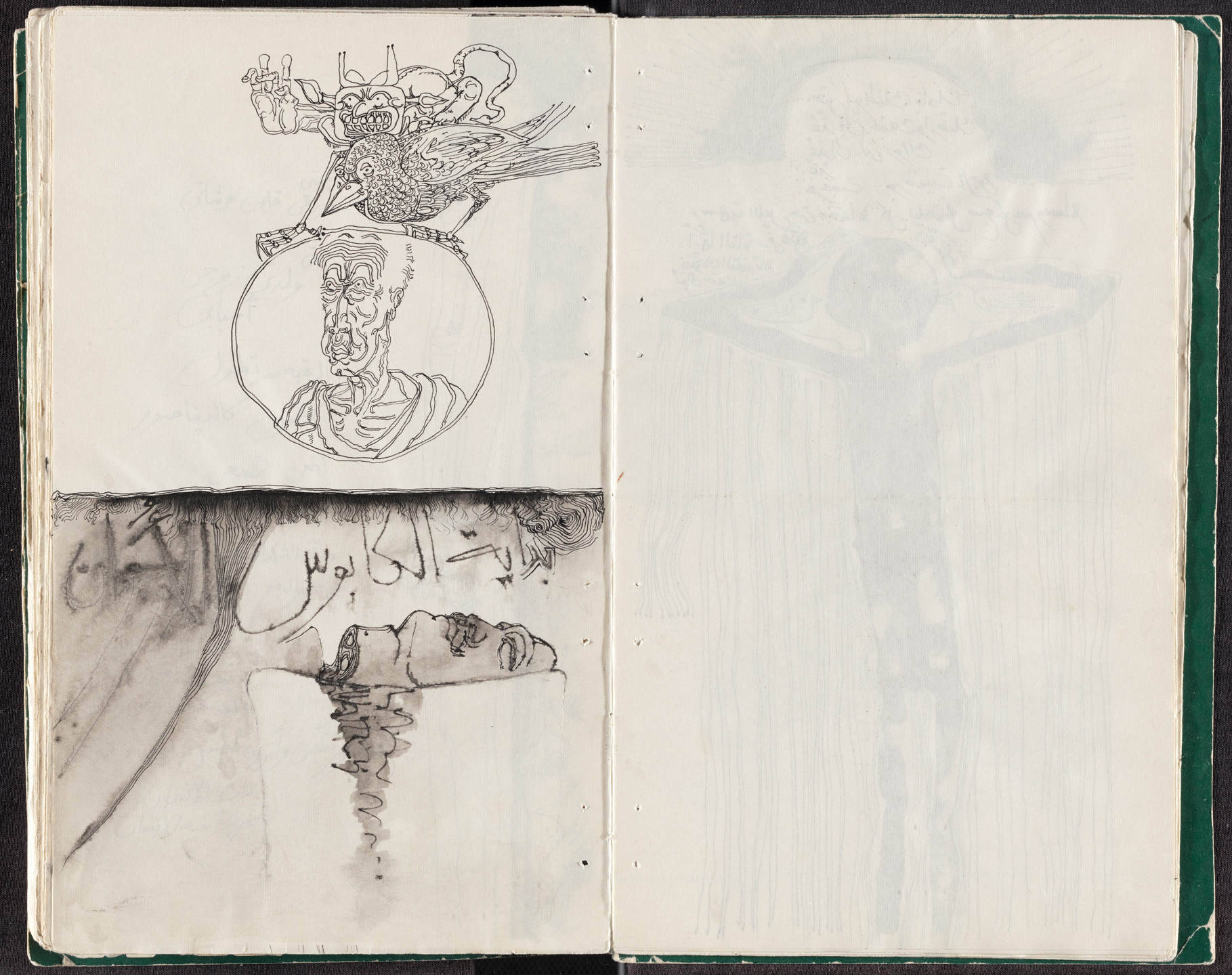

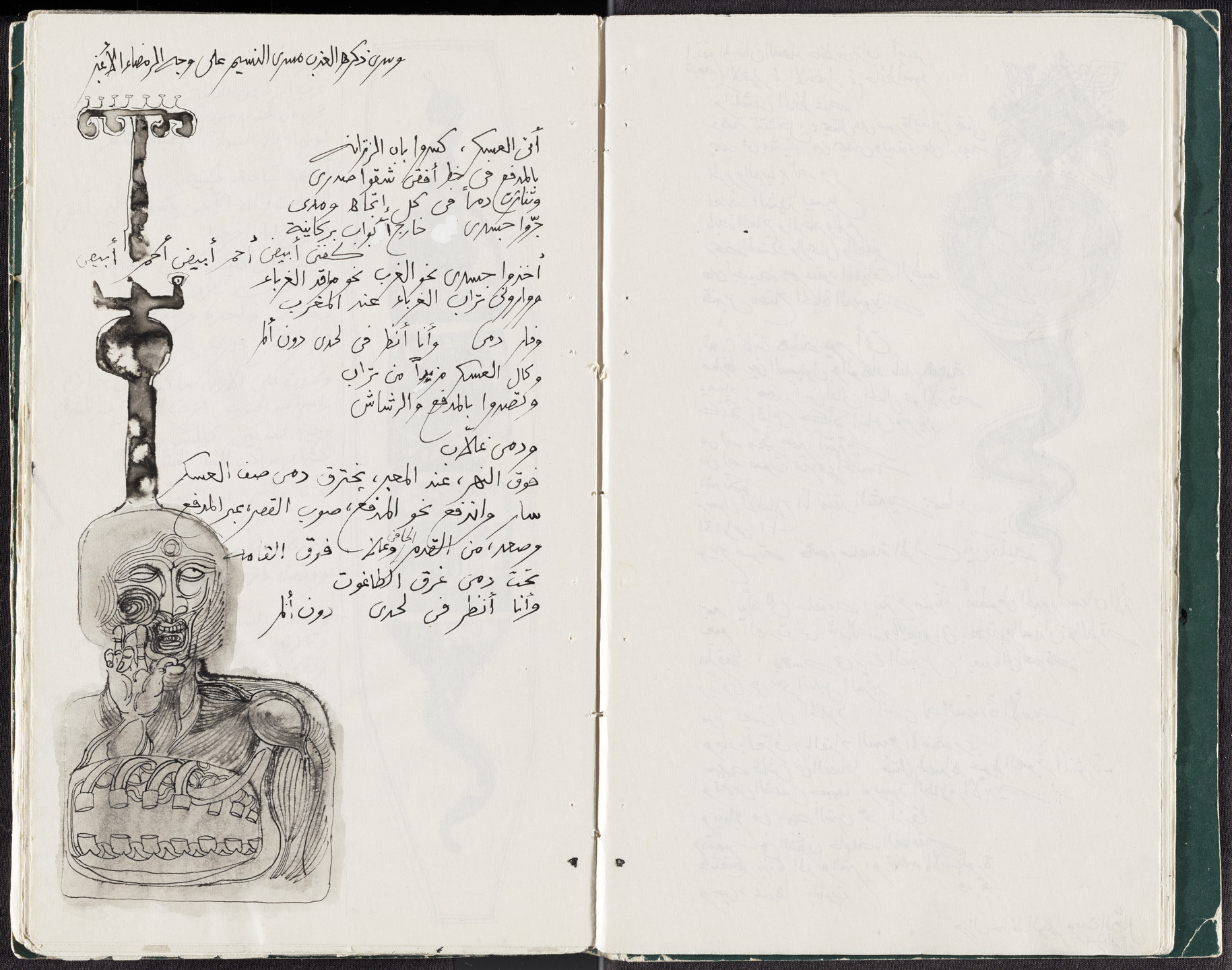

A pivotal work in the evolution of El-Salahi's creative process and artistic development, Prison Notebook also serves as a historical document, in which the artist details the brutalities that transpired under the military rule of Ja'far Nimeiri, who served as the president of Sudan from 1969 to 1985. El-Salahi recounts, for example, listening to the sound of prisoners being hanged at dawn. From his cell, he could hear their screams and "the trapdoor banging when the body . . . dropped." Conveying the torment that derived from a prisoner's perpetual sense that his own execution could be imminent, El-Salahi writes about being "escorted to interrogation" in one of his poems: Lucky is the one who would be brought back to jail. (Appears alongside the drawing portrayed in the ___ image above.) Detained in his particular jail cell—which was infested with insects, mice, and rats—were ten men "[p]acked like sardines." Among them were university professors, high-ranking judges, trade and student union leaders, and political activists whom had not "heed[ed] the instructions and directives of the regime." It was only "gradually," El-Salahi recalls, that: . . . the thin layer of foggy ignorance started to be lifted from my mind’s eye, / And I began to perceive the true essence of things.

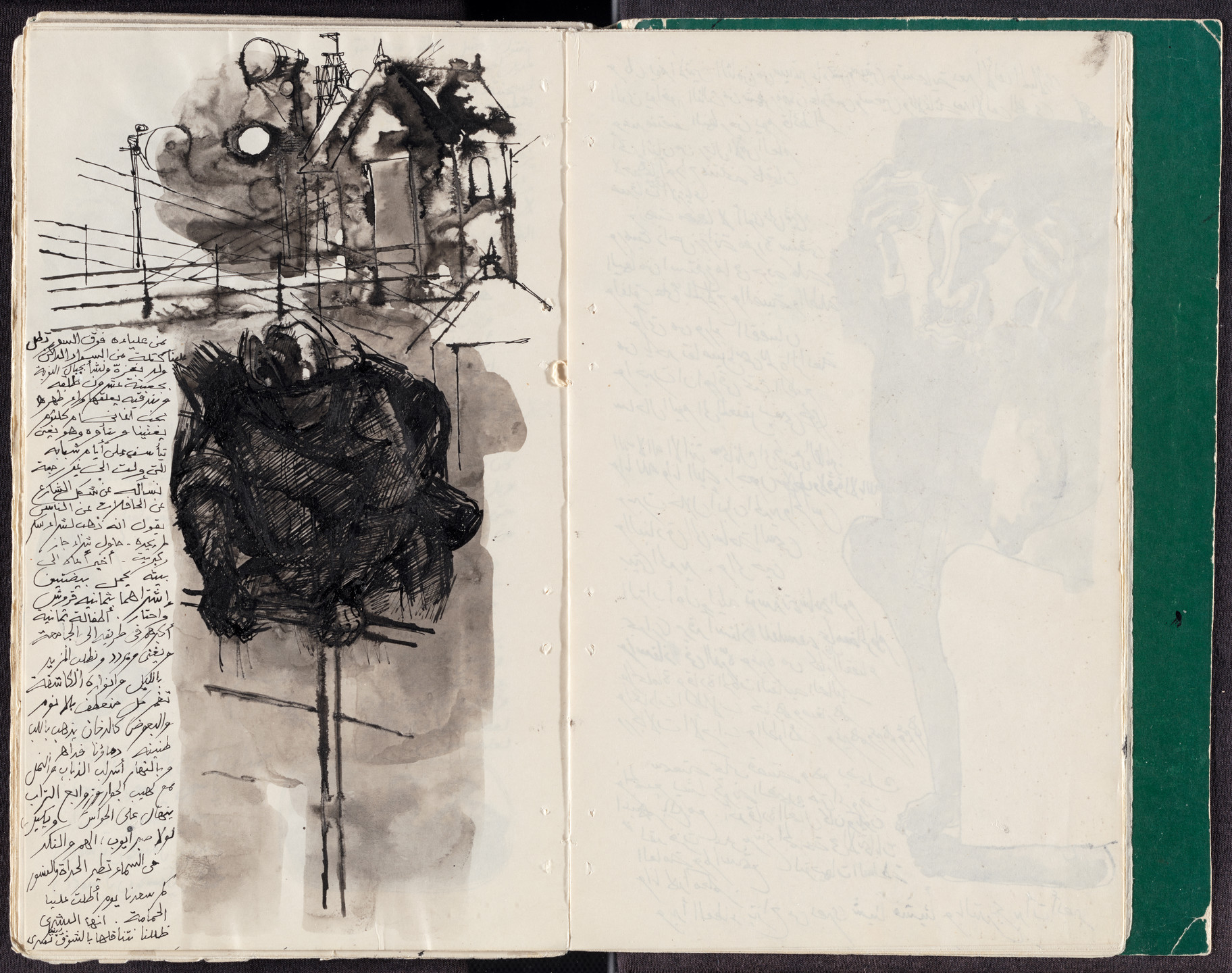

Woven together, the deeply introspective drawings and ruminations that comprise Prison Notebook lay bare the anguish that is inflicted upon the human spirit when personal self-determination is expropriated. The sketchbook conveys the internal process through which El-Salahi journeyed as he sought to reconcile individual agency with external forces antithetical to this personal sovereignty. In an essay contextualizing the ______ image above, El-Salahi writes:

I kept . . . trying to see how in certain situations you can be petrified, you can become static. At the same time, you are a human being. You have a heart, you have a mind, you have a brain. You have an apparatus within you that can show you the right way and the wrong way, so you can maneuver your destiny as you go along. But sometimes it takes you back. By the actions of others, you are made into a stone to protect yourself . . . You petrify yourself because of the situation.

Although we cannot be sure of the order in which El-Salahi originally created these sketches, the pages of Prison Notebook trace what is a remarkably linear arc of existential reflection. According to the sequential progression of the sketchbook, his trajectory begins from a point at which he felt palpably defeated by the "weight" of the power that others wielded over his life. As he describes in one of the work’s earliest pages, it was a point at which "your freedom has been taken away from you and becomes like a huge rock that is going to destroy your world, and you can do nothing—not a thing—about it." As the pages proceed, however, the drawings and poetic meditations that float across them evince an incremental yet profound transformation that ultimately leads El-Salahi to cultivate a renewed and emboldened conviction in personal autonomy and free will. In the final pages of Prison Notebook he asserts: Jail is what is accepted by oneself. There are different ways that a person can accept what is happening to him or to her. If you accept it for yourself, you are imprisoning yourself. But you can be free. . . . Remaining in prison is a personal choice.