ORDINARY WITNESSES

By Rachid Ouramdane

A one-hour dance theater piece, Ordinary Witnesses seeks to examine the physical and psychological experiences that victims of heinous brutality have endured, as well as the persisting effects and memories of such events, which survivors are forced to carry with them interminably. The production evolves through the framework of a series of personal narratives, first delineated in voice-over, then subsequently in video. In each individual testimony, the speaker reflects on various aspects of the torture to which he or she was subjected, and its impacts. One voice is followed by another, then another, collectively sharing snapshots of human suffering from Rwanda, Palestine, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile.

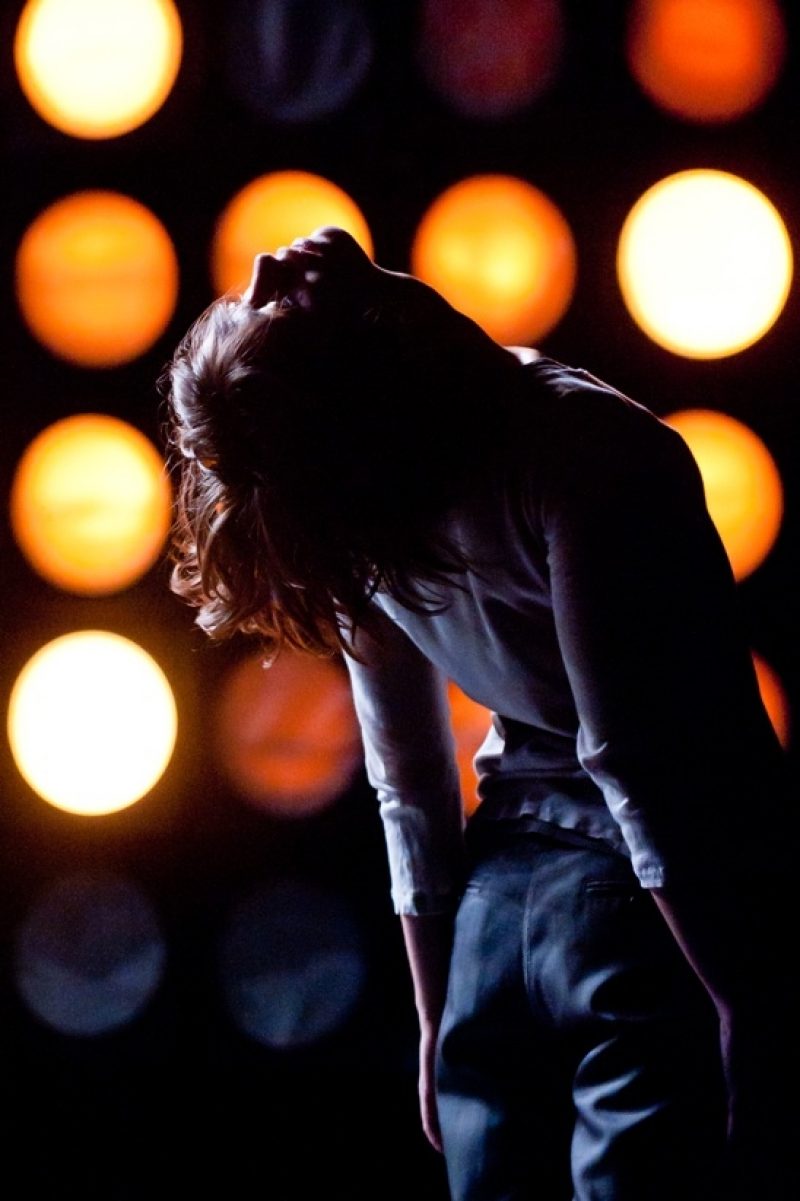

As the anecdotes and accounts cascade one after another, five dancers walk about the dimly lit stage in paths that are alienated from one another, as well as confined and repetitive, as if echoing the act of pacing inside a prison cell. Eventually, this restless roaming is abandoned, replaced with a sequence of movements that are choreographed to emulate an array of positions illustrative of the distinct stages and phases of torture and its aftermath. The performers exhibit numerous modes of collapse and breakdown, splaying themselves on the ground with limbs invariably twisted and contorted in jarring angles that are perhaps intended to be reminiscent of so-called "stress positions," otherwise referred to as positional torture. At other times, the dancers perform abstracted gestures, conveying dynamics of power and control in addition to coercion, subordination, and subjugation as some take up the role of prison guards while others assume the identity of detainees. These exchanges are ultimately brought to their conclusion when the former—with callous indifference—kick the latter into a pile of lifeless, corpse-like bodies.

The pinnacle of the piece, however, is exemplified through the protracted whirling of a single dancer. For an agonizing ten minutes, the performer spins—with arms and head bending and turning at a fluctuating velocity and in varying directions—in a sequence that appears to represent in abstract terms the physicality of dehumanization. Due to the speed and duration of her reeling, the performer’s body gradually becomes a blurred mass, stripped of its previous character and unrecognizable as a human form. When the spinning finally ceases, it is as if her body has been emptied of her former self. In this sense, artist Rachid Ouramdane attempts to express through the use of symbolic movement the sentiments that the survivors relay in their respective testimonies: namely that the acts of cruelty inflicted upon them irrefutably and irreversibly altered their inner landscape.

Ordinary Witnesses is fundamentally an exploration of and exercise in the mediums through which humanity might demonstrate the unimaginable and articulate the unspeakable. Arguably the most discernible common denominator that threads throughout the survivors' testimonies is the intrinsic and categorical inability of language to communicate the violence they have both witnessed and suffered. Even as they detail what happened to them and describe their memories, each individual notes the extreme difficulty—the impossibility—of translating his or her ordeal into speech. In this sense, the survivors explicitly acknowledge the contradiction with which they are perpetually confronted: the importance of vocalizing their suffering on the one hand, and on the other, the utter insufficiency of words.

It is this conflict that Ouramdane seeks to reconcile through Ordinary Witnesses. The artist aspires to transcend the impasse that language presents as a vehicle of expression and understanding. Recognizing the inherent limitation of words alone, Ouramdane blends them with a highly specified and choreographed amalgamation of movement, sound, and lighting in an attempt to transmit the survivors' testimonies into a more whole and integrated sensory experience. Of course, such an endeavor will—without exception—fall short, as one whom has not been tortured or brutalized can never fully understand nor imagine the pain and trauma borne by someone who has. Yet the effort and its inevitable failure are perhaps constructive in their own right, in that such underscore the alienation and corresponding isolation that survivors of war, torture, and genocide endure long after these grave abuses end. Likewise, it compels others to pause and consider a critical, albeit neglected reality: those who have lived through atrocities have witnessed and suffered horrors that make it unreservedly impossible for those who do not share an analogous experience to fully think their thoughts or feel their feelings.

Ironically, it is on this very basis that Ordinary Witnesses has been criticized. Although Ouramdane's father was tortured by electric shock in Algeria—which the artist explores in other pieces—he himself has not been subjected to such violence and cruelty. His production has thus prompted the resurgence of an ongoing discussion around the exploitation and aestheticization of other people's pain.

Video from CCN2 Grenoble's Vimeo channel