INFINITY IN BLUE

By Ayad Alkadhi

Infinity in Blue represents a natural—albeit aesthetically distinct—continuation of the themes Ayad Alkadhi explores in his previous series Al Ghareeb (2006-2008) and Father of No One’s Son (2007-2008). Each of these two earlier collections addresses—to varying degrees—the 2004 Abu Ghraib photographs, which depict scenes of torture and abuse perpetrated by American military personnel against Iraqi prisoners. Following as the third consecutive, though discrete, series to reference these images, Infinity in Blue embodies a later, more advanced phase within the perpetual sequence of action and reaction, cause and consequence that would emanate from what Alkadhi has called the “prisoner abuse scandal.” As such, the series conveys insights and reflections made manifest only through the passage of time.

The eight pieces that comprise this collection speak to the lasting and indelible repercussions that Iraqi people continue to endure, not only since the immediate aftermath of the publication of the Abu Ghraib photos, but more broadly as a result of the 2003 US-led invasion and its antecedents. The series thus serves as a testament to and a reminder of the interminable legacies of the war and occupation, and—more pointedly—of the war crimes that followed. Of course, these are legacies disproportionately borne by Iraqi civilians—innocent men, women, and children. The series bears witness to their realities in spite of—or, more likely, in response to—the palpable fact that initial global shock and outrage has long dissipated and mainstream media coverage has since pivoted elsewhere.

Thus, Infinity in Blue brings into sharp relief the temporal discrepancies that bifurcate the perennial effects of violence and trauma on one hand and, in contrast, the fleeting attention, resources, empathy, and compassion with which these effects are treated by those who are not directly affected. This juxtaposition is underscored through the artist’s use of the word “infinity” in the collection’s title. As French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas wrote in 1961, to exist “infinitely. . . means to exist without limits.” For Iraqi families and communities, that which is infinite, Alkadhi implies, is a “collective state of uncertainty and apprehension.”

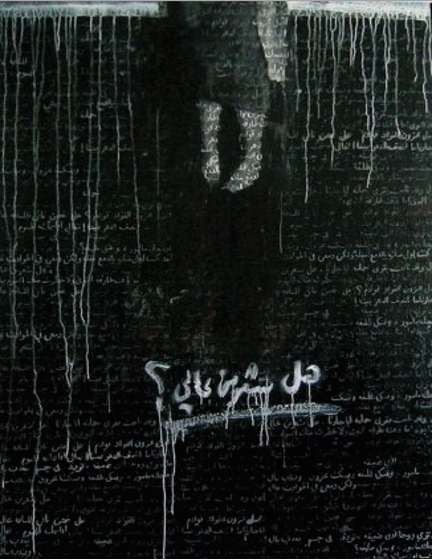

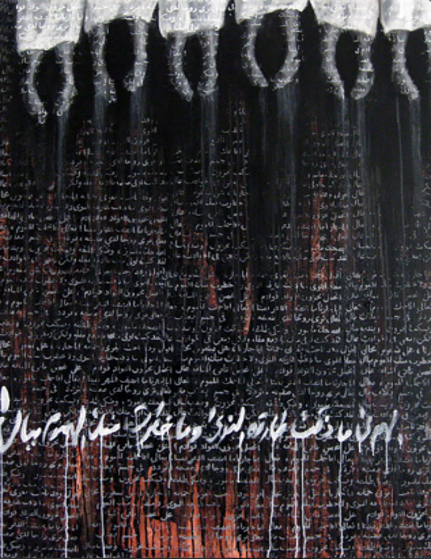

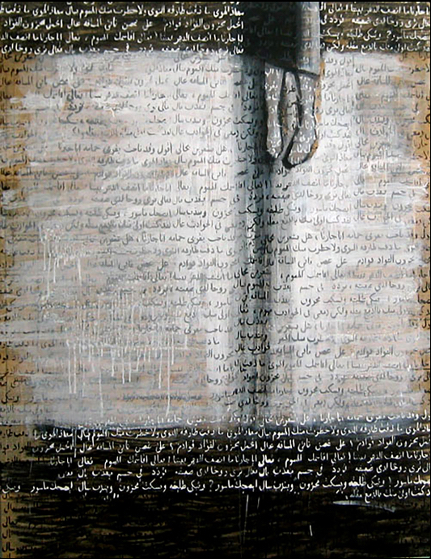

This ostensibly eternal condition is rendered through the depiction of figures suspended in various postures and from multiple placements and positions on the canvas. In one piece, the subject hangs upside-down, bound at the ankles and occupying only the bottom two-thirds of the canvas; in others, bodies dangle from the upper edge, hovering above an expanse of dense, tightly compacted lines of hand-written, largely illegible Arabic text that has been superimposed overtop Arabic language newspapers. Such positioning is employed as a visual metaphor, denoting the way in which externally-driven forces and circumstances have not only interrupted, but have categorically upended, the lives of Iraqi people. The untold corollaries of such ruptures are, as Alkadhi illustrates, ongoing and ever-present, leaving millions suspended in a time and space that is imbued with ambiguity, unease, and unfathomable, irreparable loss.

Writing in Totality and Infinity, Levinas posited that what appears to be definitive is, in fact, indeterminate when its persistence is stretched across the boundless “distance of time.” In other words, the quality of being infinite precludes definition and quantification. If we apply this sentiment to the collective state of ambivalence and foreboding that Alkadhi imparts in Infinity in Blue, then we as viewers approach a more intimate (though still removed) understanding of the implications that such a reality carries: namely, that these implications are indefinite in both duration and scope, existing in perpetuity and impervious to measurement and even explanation. Their magnitude cannot be calculated or weighed, nor articulated, and thus defy and elude rational, cognitive comprehension. The utter inadequacy of words and discursive description is, ironically, made evident through the artist’s distinctive use of Arabic newspapers, which are invariably subsumed under successive layers of content that proves more personal, more authentic, and more emotive in its expression. Through this technique—which Alkadhi employs in earlier collections, as well—he seeks to mobilize “the focus of major political headlines and redirect it toward the human [story].”

Taking in the pieces that constitute Infinity in Blue, one cannot help but recall the words of Nadje Al-Ali and Deborah Al-Najjar: “[I]t is the exception, not the rule to hear from an Iraqi about Iraq.” Alluding to decades of war, Al-Ali and Al-Najjar acknowledge that “[w]e do have cancer rates, we do know about the deaths, we do know how families have fled.” And yet—despite these facts and statistics—“[w]e have heard few Iraqi voices, limiting our ability to digest the enormity of loss and to properly mourn those losses.” Although Alkadhi began working on Infinity in Blue five years before these words were published, the series draws attention to this very reality—the reality of being unheard. Unlike the subjects portrayed in Al Ghareeb and Father of No One’s Son, the figures appearing within the pieces of this collection remain largely shapeless, their faces and bodies rendered imperceptible. This imposed anonymity—through which identity and, therefore, “know-ability” are denied—functions perhaps to both emulate and critique the way in which Iraqi people have been, in the words of Dena Al-Adeeb, “deemed invisible and marginal bystanders by dominant discourses.”

Infinity in Blue challenges such discourses, and demonstrates that to be unheard is not to be voiceless. Likewise, to be victimized and dehumanized does not in fact negate or nullify one’s humanity. In one particularly poignant and powerful piece, titled “Infinity I,” a figure is suspended over a field of black, across which lines of white, hand-written Arabic text float defiantly, though disrupted at times by paint that had run down the length of the canvas from above. Below the person’s feet—in large, legible handwriting—is a question that translates loosely to: Do you feel my condition? The verb choice (to feel) once again references the failure of words. It also, however, calls upon the viewer to place herself within the shoes of the person posing the question. In doing so, we are led down a path of countless other questions that prompt us ultimately to ask ourselves: Am I willing to feel the suffering of another? And what am I prepared to do and to change in response?