FATHER OF NO ONE'S SON

By Ayad Alkadhi

Following on the heels of Ayad Alkadhi’s Al Ghareeb collection, Father of No One’s Son extends and elaborates upon the themes of imprisonment, control, and fear, while advancing a more categorically political and incisive commentary on the US invasion of Iraq and the torture of Iraqi prisoners detained at Abu Ghraib. Photos capturing this torture—which were released in the spring of 2004—endure as evidence of US-perpetrated, state-sanctioned war crimes, and immediately and decisively exposed the myth of American exceptionalism and moral superiority. Long promoted via government rhetoric and an uncritical and even excusatory media industry, it is this myth that Father of No One’s Son interrogates and critiques.

Alkadhi often describes himself as a “visual storyteller.” The stories he relates, however, challenge—rather than conform to—the sanitized statements and banal platitudes and essentialism reiterated by American government and military officials, and often subsequently parroted by mainstream, commercialized media outlets. Throughout his career, Alkadhi has consistently and unabashedly inserted his astute artistic voice into the forum of public opinion, interrupting conventional narratives and calling into question orthodox discourse in order to, as historian Howard Zinn wrote, “go beyond and escape what is handed down” by those in positions of power. Nowhere does Alkadhi “transcend the word of the establishment” more cogently and assertively than within the three pieces that constitute Father of No One’s Son.

As intellectual Susan Sontag accurately anticipated, the photographs taken at Abu Ghraib are today not only irretrievably linked to, but remain perhaps the most prominent symbol of the US invasion of Iraq and the war that ensued thereafter. Indeed eighteen years after their publication, these photos of torture persist as the American occupation’s “defining association,” cemented within the minds of “people everywhere.” Alkadhi expertly draws upon this association, invoking the Abu Ghraib images not only to bring into focus the brutality that they depict—which the prevailing US discourse largely trivialized and dismissed—but also to examine America’s presence in Iraq more broadly.

In the first piece featured above, Alkadhi lays bare what he perceives to be the real motivation behind the 2003 invasion. Titled “Price of a Barrel,” the work alludes to Iraq’s lucrative oil fields, while emulating in its visual composition the single-most notorious photo to emerge from Abu Ghraib. In the photograph—published by The New Yorker on 30 April 2004—a hooded man stands atop a narrow box, balancing with outstretched arms. Attached to his hands are wires, which he was told would deliver electric shocks to his body if he lost his balance and fell. Alkadhi’s work likewise centers upon a man dressed in a black hood with raised arms—though now a face is visible and is that of the artist himself. His eyes peer directly into the ‘camera’ of the soldier photographing his anguish. In this sense, the subject of the work defiantly bears witness to his torture as well as his torturers, all the while waiting for anyone—captors, guards, spectators, onlookers, those actively participating in his suffering and those who are complicit in their complacency—to meet his unflinching gaze.

The photograph to which this particular work refers is not only the most infamous of the Abu Ghraib collection; the image has also become emblematic of the extraordinary rendition (unlawful transfers), “black sites” (secret or incommunicado detention), and torture in which the US engaged in the name of its so-called “War on Terror.” Thus, by invoking this photo specifically, Alkadhi draws attention to the litany of international law violations perpetrated by the US in the aftermath of 9/11, and—by extension—points out the absurdity of official rhetoric, which ceaselessly marketed the Iraq War as the linchpin of future democracy and human rights in the region. In linking the Abu Ghraib atrocities to Iraq’s oil reserves, “Price of a Barrel” exposes the George W. Bush administration’s humanitarian narrative for what it really was: a pretext on which to legitimize the US invasion and a guise under which to conceal ulterior economic and geo-strategic aims.

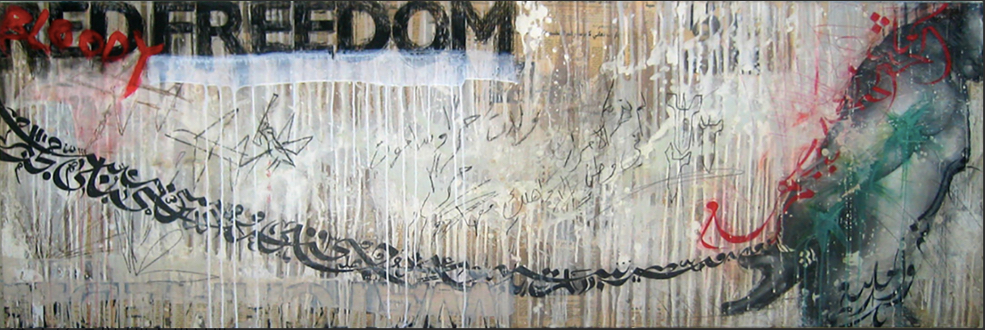

The cynicism and irony of this discourse is further highlighted in the second piece featured above. The artist himself is depicted on the right side of the canvas, now naked with hands bound behind his back. Written in the upper left-hand corner, out of the subject’s view, are the words “Bloody Red Freedom”—the title of the work, and perhaps a reference to the hypocrisy of the March 2003 US-led invasion, which was euphemistically dubbed “Operation Iraqi Freedom.” The reality of the war, as experienced by Iraqi people, is more accurately (and honestly) captured in the Arabic, graffiti-style writings and drawings that are scrawled in the background of the piece, which do not allude to symbols of liberty or human rights, but instead portray fighter jets and falling bombs.

This work is reminiscent of those that comprise Alkadhi’s earlier Al Ghareeb series (2006-2008), particularly in its use of the Arabic calligram, which once more forms the shape of the chain that extends from the subject’s bound wrists. Alkadhi has often described his use of Arabic calligraphy “as a bridge to Middle Eastern heritage and culture.” Thus, in employing calligraphy as the mechanism by which the subject is chained or shackled, Alkadhi is suggesting that it is one’s real or perceived belonging to Middle Eastern or Arab heritage and culture that serves as the grounds on which he can be detained, imprisoned, and denied his most basic rights and freedoms. In other words, Alkadhi’s distinctive application of the Arabic calligram implies that the abuses perpetrated inside Abu Ghraib were carried out merely by virtue of the prisoners’ language, ethnicity, and culture. This assertion, of course, has been echoed by countless others. Indeed, in the days following the publication of the photos, Susan Sontag noted that the Americans responsible “believe that the people they are torturing belong to an inferior race or religion.” Likewise, art historian and cultural critic Dora Apel observes that the torturers photographed in the Abu Ghraib images were convinced that they were acting “in defense of a political and cultural hierarchy.”

Yet “Bloody Red Freedom” invokes the rich cultural, religious, artistic, and architectural heritage that Arabic calligraphy embodies, and situates it in juxtaposition with the debased, deep-seated prejudice demonstrated by the American military establishment. In so doing, Alkadhi challenges western assumptions regarding the basic imperatives of human decency, and thus turns on their head discriminatory tropes that have long espoused what it means to be ‘civilized.’

Islamophobia has, for decades, featured prominently within such tropes, functioning to cast Islam as a faith inextricably associated with, and sympathetic to, terrorism. Alkadhi’s appropriation of Christian symbolism and iconography is therefore exceptionally powerful. “Cross to Bare,” the third and final piece within this series, calls to mind scenes and imagery rendering the crucifixion of Jesus. Reflecting upon the origins and inspiration for the work, the artist recalls listening to the mother of one of the men depicted in the Abu Ghraib photos. Appearing on Arabic-language television, the woman was asked to recount how she felt upon seeing her tortured son in the images. She responded by likening her helplessness and devastation to that which she imagined the Virgin Mary had experienced as she looked on as Jesus was crucified.

Yet, as artist and academic Safdar Ahmed observes, although “Alkadhi’s tortured body resembles the broken figure of Christ [in “Cross to Bare”], there is no resurrection: no providential or otherworldly end for the victim of … foreign imperialism.” On the contrary, the west’s ‘counter-terrorism’ praxis has both reinforced and relied upon a “process of dehumanization” that, as Dora Apel has written, “makes [Arabs and Muslims] far easier to humiliate, torture, sexually exploit, and kill.” Also drawing parallels between the tortured prisoners of Abu Ghraib and the tormented body of Christ, Apel concludes: “The US military, although claiming the moral high ground … [has] assumed the position of Roman torturers, crucifiers, [and] persecutors.”

Father of No One’s Son fundamentally re-contextualizes the Abu Ghraib images and the overarching US torture program in which the photographed abuses are rooted. Through his masterful use of sarcasm and symbolism, Alkadhi delivers a searing response to an American narrative devoid of meaningful acknowledgement, much less accountability. Both aesthetically and intellectually provocative, each piece within this collection offers myriad layers of meaning and suggestion, and therefore untold opportunities for analysis—goading even the most unwilling of viewers to contemplate the US presence in Iraq through an altered lens, and thus—in Alkadhi’s own words—“prompting them to question their ideals.” In the process, Alkadhi illustrates that those responsible for the Abu Ghraib atrocities personify that which they themselves so vehemently purport to oppose.